In the beginning, there was Riesling. That is to say, when I first got into the business in the mid-1970s; the days when wines like Cold Duck, Blue Nun, Mateus, Lambrusco, and Chenin Blanc were our best sellers, Chardonnay (then called “Pinot Chardonnay”) was an obscurity, Merlot unheard of, and White Zinfandel wasn’t even invented.

In the beginning, there was Riesling. That is to say, when I first got into the business in the mid-1970s; the days when wines like Cold Duck, Blue Nun, Mateus, Lambrusco, and Chenin Blanc were our best sellers, Chardonnay (then called “Pinot Chardonnay”) was an obscurity, Merlot unheard of, and White Zinfandel wasn’t even invented.Tastes were simpler then – all most people wanted was something soft, light and nectarishly sweet. So when we needed to upgrade our guests, we would turn them on to German Rieslings from great vineyards like Doktor, Sonnenuhr, Vollrads, Johannisberg, and Scharzhofberg; and generally speaking, these vineyards’ medium sweet spätlesen were the most popular. Definitely an upgrade over Blue Nun and Mateus.

Then came the early 1980s, and with the introduction of $5 Glen Ellen and $8 Kendall-Jackson Chardonnays, consumers fell into somewhat of a deep end. Wine appreciation suddenly became a game of show-and-tell; or as one syndicated writer put it, like wearing shirts with someone else's name on it. The bigger, more prestigious and pricier the wine, the better. $35 Chateau Montelena and Peter Michael Chardonnays eventually led to $75 Turley Zinfandels, $150 Beringer Private Reserves, and $500 Grace Family Cabernet Sauvignons. Why mince words? Connoisseurship lapsed into upmanship, and the stupidity has grown unabated ever since.

What happened? Bonny Doon’s winemaker/proprietor, Randall Grahm, once blamed it all on the popularity of Chardonnay. I think he still calls the grape the “Vintichrist… a symbol of our degeneration into cholesterol-infused mania.”

I don’t think Chardonnays, or Turley Zinfandels and Napa Valley Cabernets, are inherently bad. But I sure do miss the days when wine drinking was simpler. When, like eating quiche and driving Beetles, we could still boast about enjoying a great Piesporter Goldtöpfchen rather than a 98-point wine. It’s a shame, says Grahm, that Riesling came to be perceived as the “nerdiest possible grape” when, in fact (to Grahm, at least), it is the “very hippest.”

Strange days indeed; since Riesling, in fact, has become cool again; like white lightning and leather boots, as Merle Haggard sang, "still in style for manly footwear." In one of his newsletters a few years back, Harry Peterson-Nedry of Oregon’s Chehalem Vineyards went absolutely ga-ga in his description of the grape:

Riesling is a dancer… a Mia Hamm… a lithely elegant Audrey Hepburn or firmly aristocratic Katherine Hepburn. Like the world of grace, manners, reserve and contemplation… Riesling has been neglected… deferred to a competition of wines made in macho proportions, wines on steroids like oak and alcohol and extract.

Riesling is a dancer… a Mia Hamm… a lithely elegant Audrey Hepburn or firmly aristocratic Katherine Hepburn. Like the world of grace, manners, reserve and contemplation… Riesling has been neglected… deferred to a competition of wines made in macho proportions, wines on steroids like oak and alcohol and extract.Give ‘em hell, Harry. If anything, the finest Rieslings are the direct opposite of pumped-up Chardonnays and 200% new-oaked Cabernets. The best are light, delicate, wickedly sleek, often cuttingly dry and just as often meltingly sweet, yet almost always brightly acidic, even nervy. A tale of two Hepburns, as it were.

So why drink Riesling today? Thirty years ago we unabashedly enjoyed Riesling precisely because of its inherently sweet and delicate nature; and the very best of that style, of course, always came from the Germany, where the cool climate (the coldest in the world for growing grapes) gives the natural acidity necessary to balance wines with residual sugar.

But the fact of the matter is that, during the past twenty years, more than 90% of Germany's Rieslings have been produced in dryer styles – bottled as trocken (“dry”) or halbtocken (“half-dry) – similar to the style of Riesling traditionally produced in France’s Alsace region. Why? Because people in Germany, like much of the world, now prefer it that way; particularly to go with their increasingly internationalized taste in food.

In 1998, when I first visited Bernkastel-Kues on the Moselle River, I found it almost ironic when I asked Johannes Selbach (owner of the Selbach-Oster winery) which restaurant I should go to for the best selection of local wines, he said, "Why, that would be the Indian restaurant near the center of town.” Even in the fairy tale wine country towns, Germany is much more than sauerkraut, liver dumplings, and blood sausages.

Despite the association of Riesling with Germany, this late budding grape has also been known to perform quite well, thank you, in regions as diverse as Alsace in France and Stellenbosch in South Africa, Austria and Australia, from the lakes of New York to the shores of New Zealand, British Columbia's Similkameen and Southern Oregon's Umpqua Valleys, in Georgia our fourth state and Georgia the post-Soviet state, and elsewhere. What little there is left in California can still produce a zingy, billowingly perfumed wine. In warmer climates Riesling may produce fuller, fruitier, less finely etched whites than in Germany; but no one would describe, say, a Clare Valley or Columbia River-side Riesling as fat or flabby; but in fact, the opposite, lean and limber, like either Hepburn. When farmed with care, and picked early enough, Riesling retains plenty enough balancing acidity virtually everywhere it is found.

It is precisely because of the wine’s intrinsic, undiminished beauty that Riesling has definitely been making a comeback. Not exactly a Waimea Bay sized wave of a comeback; but definitely a noticeable bit of a turning tide, washing up between our toes, to the occasional amusement of even many Chardonnay and Cabernet drinkers. And if anything, much of the recent resurgence has been for culinary reasons.

THE IDEAL RIESLING FOOD MATCHES

Is Riesling the greatest single white wine for food? If you go by the tried-and-true premise that intrinsically balanced wines of any type tend to go better with food, it may very well be. No, Riesling cannot leap tall buildings (or at least, tall orders of foods) in a single bound. But it is Riesling’s naturally fresh, lithe, vibrant balance of acidity and fruitiness that tend to make it an easy match with the oft-times fatty, sweet, soured foods of traditional Germany.

Some observations on Riesling as a food match; why and when it works:

* It is good to have a wine that easily echoes the balance of sweet, sour, salty or spicy condiments like salsa, dips and relishes, often served to enhance white meats

* The lightness, sugar/acid balance and floral fruitiness of Riesling makes it an easier wine than others to match foods incorporating anise or licorice-like herbs such as cilantro, tarragon, Thai basils, Mexican mint marigold, dill and chervil; variant but strong seasonings like capers, anise, ginger and coriander; and other dominating ingredients such as alliums, fennel, sorrel, ginger, chiso and lemon grass

* Few wines carry sweetness as well as Riesling, and so it goes without saying that this quality allows Riesling to go where other wines can’t -- balancing hot spices (the entire, multi-cultural range of chile derived oils, pastes and spice mixes), saltiness (soy sauce based marinades, dips and sauces, seafood stocks, seaweeds, oyster sauce, cured meats, briny fish, gravlax, and so forth), sourness (seviche, tamarind, ponzu, pickled vegetables, fresh citrus, pomegranate, kaffir, all vinegars, even “thousand year old eggs”), as well as mild bitterness (vegetables like kaiware, Chinese broccoli and cabbages)

* Be as it may, in our experience we’ve found that the best Rieslings for balanced foods that express the full range of taste and tactile sensations are those that are either barely sweet or else completely dry! Riesling is an intense enough grape to project flowery fruitiness even without the presence of residual sugar, yet with a finer, cleaner, crisper sense of balance than other aggressively scented varietals (such as Gewürztraminer, Viognier and Muscat Blanc)

* One would also assume that when a dish contains sweet components, it makes sense to match it with a slightly sweet to medium sweet Riesling (approximately 1.5% to 4% residual sugar); but again, we have found this to be not true. When dishes are already balanced with residual sugar, it is almost preferable that a Riesling be either dry or just whispery sweet (between .6 or 1.5% residual sugar, depending upon the wine’s strength of balancing acidity), as anything sweeter than that tends to make residual sugars in a dish redundant (rendering the entire combination of food and wine unbalanced or cloying)

* It is worth noting that Riesling also does well with smoked or cured foods (like trout, salmon, and even pork or poultry)

* It is for these reasons that Riesling easily matches many of the globally styled foods we enjoy today that were once perceived as “impossible” wine matches: hot curries, chile laced sauces, sweet/sour barbecues, salty shoyu dips, herby salad vinaigrettes, and umami intense vegetables (such as mushrooms, seaweeds, and vine ripened tomatoes) and meats (especially raw fish and slow cooked “other white” meats)

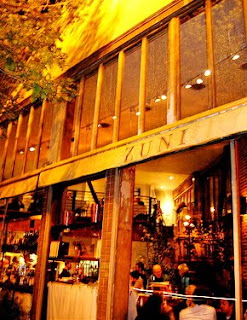

* Again for the same reason, Riesling is especially apropos in contemporary restaurants driven by classically trained, but multi-cultural inspired, chefs who almost invariably incorporate ingredients that give hot, sour, salty, sweet or even bitter sensations. Why? These are the restaurants we enjoy the most!

Balance of acidity, lightness, and food versatility are not the only qualities of classic Rieslings. What’s wrong with a wine that actually tastes great by itself? After all, the perpetually lush, peaches-and-cream fruitiness of Riesling is as fresh and inviting to the palate as a proverbial spring day. Who doesn’t enjoy the taste of spring – winter, spring, summer or fall? In other words, Riesling is as much a wine for all times and all tastes as for all kinds of foods.

Comments

Post a Comment